European governments are not alone in wondering how to deal with digital giants

TALK to Axelle Lemaire, a French secretary of state in charge of all things digital, and one topic quickly comes up: online platforms of the kind operated by tech giants such as Facebook, Google and Uber. “France is very open to them,” she insists, “but consumers have to be protected.”

Ms Lemaire’s words will soon be put into action. The French parliament is about to pass a law, sponsored by her, which will create the principle of loyauté des plateformes, best translated as platform fairness. Once it takes effect, operators of online marketplaces will, among other things, be required to signal when an offer is given prominence because the operator has struck a deal with the firm in question, as opposed to it being the best available.

In Brussels, too, the regulation of platforms is on the agenda. On May 25th the European Commission announced plans for how it intends to deal with such services. Its proposals cover everything from what tech firms should do to rid their digital properties of objectionable content, such as hate speech, to whether users can move data they have accumulated on one platform to another.

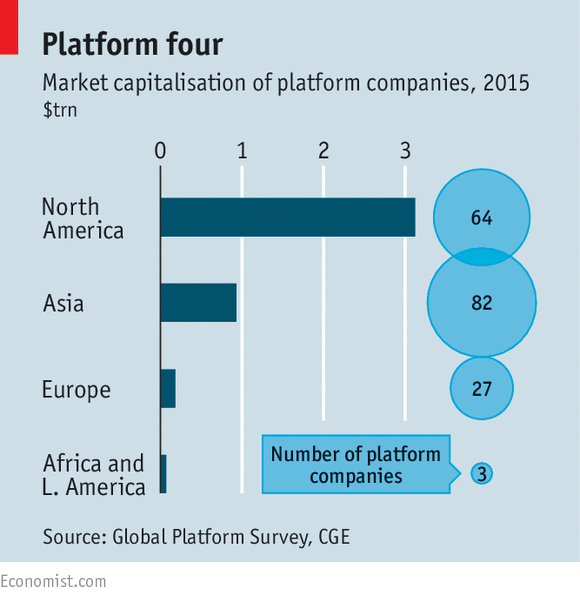

Here we go again, many will say. As usual, Europe is putting regulation above innovation, and being protectionist to boot, since most platforms are either American or Asian (see chart). European firms earned only about 5% of the profits of the 50 biggest listed platforms, which reached a total of $1.6 trillion in the past four years; more than 80% ended up in America. The commission has been going after American tech firms for a while, say critics—it will soon decide how to punish Google for abusing its dominance in internet search, for example. This week’s plan fits a pattern.

Here we go again, many will say. As usual, Europe is putting regulation above innovation, and being protectionist to boot, since most platforms are either American or Asian (see chart). European firms earned only about 5% of the profits of the 50 biggest listed platforms, which reached a total of $1.6 trillion in the past four years; more than 80% ended up in America. The commission has been going after American tech firms for a while, say critics—it will soon decide how to punish Google for abusing its dominance in internet search, for example. This week’s plan fits a pattern.

But it is not only Europe that is suffering from growing platform anxiety. Although worries vary, politicians and regulators around the world are waking up to the power of these online matchmakers, whose role is to bring together different groups—advertisers and consumers in the case of Facebook and Google, merchants and buyers in the case of Amazon, drivers and passengers in the case of Uber. Platforms exhibit what is known as “network effects”: the bigger the number of one kind of customer, the more attractive these services are for the other sort, and vice versa.

Facebook, the world’s biggest social network, symbolises the rise of global platforms. It now boasts over 1.65 billion active users a month worldwide—more than the population of China. On average, they spend about 50 minutes per day on the site and the other two big services Facebook owns, Instagram and WhatsApp. For many of its users, the social network is not only useful for connecting with friends and relatives but also an important news source.

Platforms have also started to emerge in other sectors. Industrial machines and their products are packed with sensors and connected to the internet, digitising the real world and creating opportunities for matchmakers to connect manufacturers with suppliers. (This is where the EU sees a chance to close the gap with America.)

If Europe, predictably, is reacting to the rise of platforms through the rule book, America’s response also fits a stereotype. Regulators have largely given the country’s platforms free rein—which may not be unconnected to the fact that they are now fervent lobbyists. In 2013, for instance, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which had been scrutinising Google, decided to take no action. But private actors are flexing their muscles.

The platlash

Platform operators have faced a barrage of class-action suits from private litigants. Last month Uber, a taxi-hailing service, settled one brought by drivers, promising no longer to kick them off its app without warning or recourse. After pressure from consumer groups, Google announced on May 11th that it would ban adverts for payday lenders, which are widely viewed as exploiting their customers.

The debate about the power of platforms has grown more heated thanks to reports this month that Facebook employees have kept news topics on issues close to conservatives’ hearts away from prominent display. Many, on both right and left, have called for Facebook, which denies the allegations, to be reined in. When a group of conservatives recently met Mark Zuckerberg, the firm’s boss, some demanded that it should have a more politically diverse workforce and take into consideration the impact on businesses when it changes the algorithm that decides if their Facebook page is shown in people’s newsfeeds.

Now the regulatory winds may be shifting. The FTC seems to be having second thoughts: it is investigating whether the firm abuses its dominance in mobile operating systems. Whoever is elected president in November is unlikely to ignore the question of platforms. “If I become president, oh do they have problems,” Donald Trump has said of Amazon, accusing it of evading taxes.

The mood is changing in Asia too, albeit more slowly. In recent years the size of Naver, a web portal in South Korea, has prompted debate about whether it should be regulated. After an investigation by the country’s watchdogs, the firm has agreed, among other things, to help smaller online firms sell their wares.

The Chinese government is making life harder for platforms—and not just big Western ones, many of which are banned in the country or kept out by its Great Firewall. Alibaba, Baidu, Tencent and other big Chinese internet firms already know what is expected of them when it comes to keeping their services free of politically sensitive content. But other concerns are also increasingly to the fore: earlier this year Baidu got into hot water after the death of a student who said he had received misleading information on a cancer treatment from the company’s search engine. The government may seek even greater control over online-video platforms by insisting on taking minority equity stakes.

The European Commission’s plans don’t go that far but some proposals could end up being very interventionist (the details are still being worked out). For instance, the commission intends to create a “level playing field” for conventional telecoms carriers and firms that offer communication services over the internet, such as messaging apps. The question is whether levelling the field would involve lightening the regulatory burden on incumbents, such as the requirement to offer universal service, or applying such rules to newcomers. If the commission’s intentions for on-demand video services, such as Netflix, are any guide, the newcomers are likely to face new responsibilities: it wants to ensure that 20% of content is European.

In most other respects, however, the plans are a far cry from the fiery rhetoric in late 2014, when the European Parliament passed a resolution for Google to be broken up. In fact, they are notable as much for what they do not say as what they do. They do not, for instance, seek to make platforms responsible for illegal activities on their properties. Such “platform liability” would hurt small (mostly European) ones more than big (mostly American) ones, because there are economies of scale in policing this sort of thing. Instead, the commission is betting mainly on self-regulation to keep platforms clean (although it says it might take “additional measures” should such voluntary efforts fall short).

Another notable absence is a plan to apply new competition rules across all types of platform. Last year France and Germany, in particular, had demanded such “horizontal legislation” to strengthen the rights of smaller businesses that have come to rely on platforms—for instance, to keep platforms from imposing unfair terms and conditions or changing them unilaterally. But given the diversity of platforms, the commission has opted to stick with existing competition law and look at problems on a case-by-case basis. (In a nod to more interventionist member states, however, it plans to revisit the question next year).

The most interesting questions concern how platforms collect data from users and connected devices. These help firms improve services and target ads. But they can also be a source of market power—something antitrust experts have only now started looking into. “Exclusive access to multiple sources of user data may confer an unmatchable advantage,” warns an influential report by a committee in Britain’s House of Lords. Germany’s competition authority is investigating whether Facebook has abused its dominance to impose weak privacy rules on users.

Sensibly, given how little is known about the mechanics of data markets, the commission intends to take only limited steps. For instance, it wants online firms to give users the option to log in using government-issued IDs rather than credentials provided by big platforms. This could make it harder for these to track users as they move around the internet, limiting their ability to scoop up data from sites belonging to others. Another proposal is to make it easier, for both consumers and businesses, to transfer data if they want to switch platforms.

Regulators still have much to learn about how to deal with platforms. But they have no choice but to get more expert. As Martin Bailey, who heads the commission’s efforts to create a single digital market, told the Lords committee: “There is hardly an area of economic and, arguably, social interaction these days that is left untouched by platforms in some way.” That is true far beyond the borders of Europe.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the FTC is again looking into Google’s search business.

Fonte: Economist